Hi, and welcome to this video about the hydrologic cycle!

Today, we’ll be looking at all the different processes involved in this cycle and what effect it has on the earth.

The hydrologic cycle, or the water cycle, describes the processes by which water molecules travel from the surface of the earth to the atmosphere, back to Earth’s surface over and over again. The water cycle is powered by the sun and showcases a continuous exchange of moisture between land, oceans, and our atmosphere.

Processes and Phases of the Water Cycle

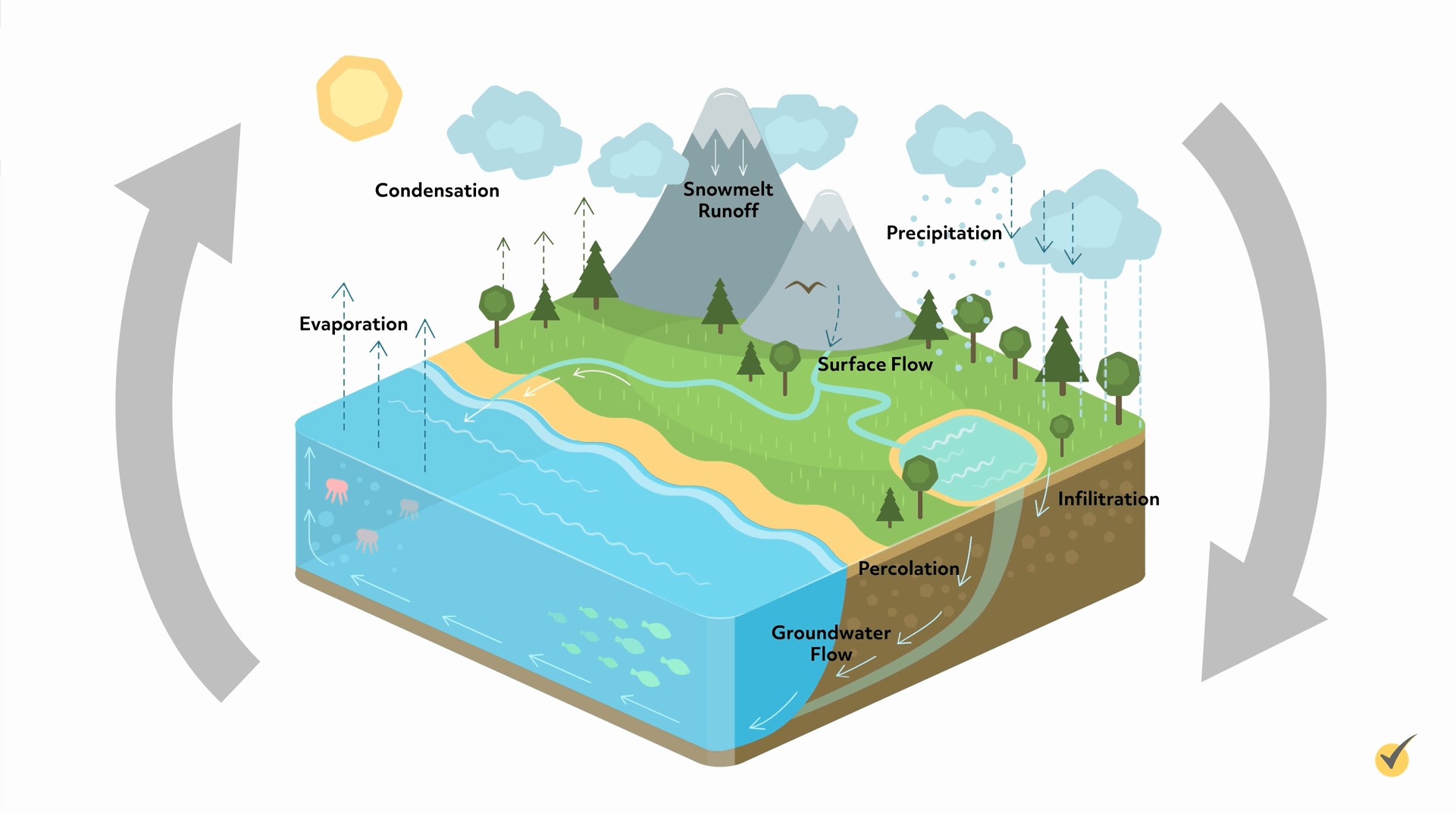

This diagram of the water cycle shows the majority of its phases. We will go into most of these in depth in a few minutes, but for now, let’s just discuss the water cycle at a 30,000-foot view starting on the left side of this picture.

The sun is the energy source that powers this whole process. Water that is in our oceans is evaporated by the sun into our atmosphere. Once these water droplets are lifted to a certain height, called the lifting condensation level, they will condense and form the clouds that we see in the sky. Condensation is the change in the state of water from the gas phase to the liquid phase.

When clouds become saturated with water droplets, they may release precipitation either back over the oceans, where this short process will repeat indefinitely, or over land, where it gets much, much more complicated. In either case, precipitation can be in many different forms – rain, snow, hail, sleet, and a lot of other things in between.

Alright, so now we’re over the top of the mountains in this picture. If precipitation falls in places like this, where there are snow-capped mountains, the snow will continue to accumulate until it melts, at which point you’ll have snowmelt runoff, which is a type of surface flow. Surface flow is any water that flows on top of Earth’s surface. Any type of surface flow will eventually find its way to a body of water; whether that’s a stream, pond, lake, river, ocean, et cetera. In this case, the surface flow leads into a little lake.

In the middle of the picture, you can see a river flowing back into the ocean where, like we talked about before, the short process of evaporation, condensation, and precipitation create an infinite cycle. For now, let’s go back and focus on the little lake and the area around it. You’ll notice that evaporation is happening, just as it does with any lake, pond, or any other body of water. But look at the cross-section view beneath the lake. You’ll see two processes called infiltration and percolation, which are very similar, but not exactly the same.

The process of infiltration is simply the downward movement of water into Earth’s subsurface, while percolation is the downward movement of water through porous or cracked rock. In either case, water will eventually end up beneath Earth’s surface, where it will continue to flow toward the ocean. You can see this indicated in the diagram as groundwater flow, but it’s also known as subsurface flow.

Subsurface Flow

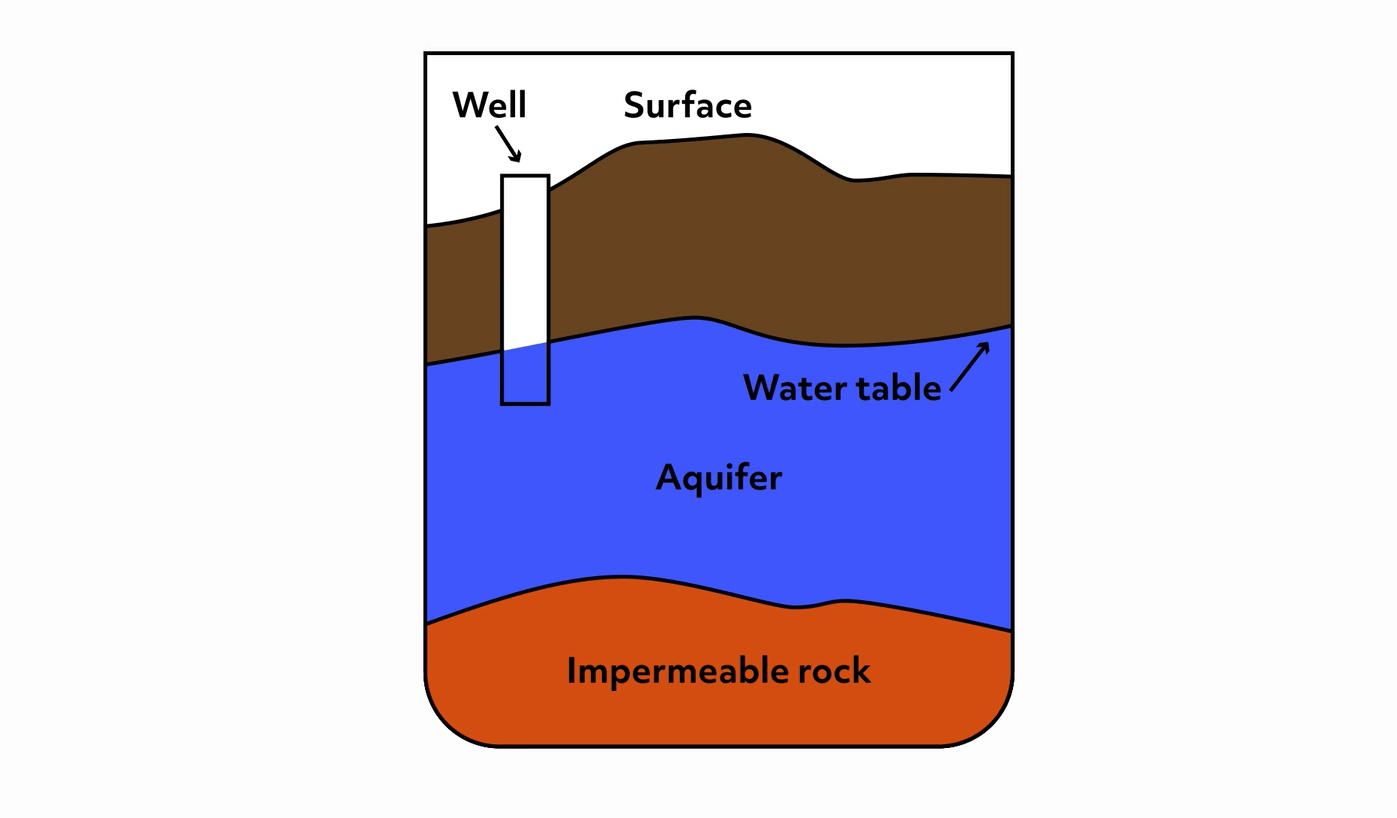

Let’s focus on groundwater flow for a little bit. A huge amount of groundwater is stored in layers of permeable rock known as “aquifers”. It looks something like this:

You can see here that an aquifer lies beneath Earth’s surface, but above an impermeable rock. Impermeable means the water cannot seep through it and infiltrate any deeper. You’ll also see a well that has been drilled to gain access to the water found in the aquifer. The important thing to note here is that an aquifer is always located beneath the water table.

Have you ever dug a hole in the sand at the beach? After maybe a foot or so, it starts to fill up with water. Congratulations, you’ve found the water table! The water table is simply the depth at which Earth’s subsurface is saturated with water. The water that has just come through the hole you dug is part of an aquifer.

Let’s leave the beach and go further inland. As water travels beneath Earth’s surface, it can be taken up through roots to provide sustenance to plants. The excess water remaining when the plant has used all it can then evaporates into the atmosphere from its leaves, flowers, or stems. This special type of evaporation is referred to as transpiration. The sum of evaporation on earth’s surface and transpiration is collectively referred to as evapotranspiration.

When precipitation is blocked from reaching the ground by a tree canopy, it’s called canopy interception. Because this water isn’t coming through plants’ roots, it can’t be used by the plant, so it subsequently just evaporates back into the atmosphere.

Now that we’ve seen the main processes of the hydrologic cycle, let’s take a closer look at the different stages of water itself.

We all know that water has three phases: solid, liquid, and gas. We know that liquid water evaporates into water vapor, and water vapor condenses into liquid water, and liquid water freezes into ice. However, there are a few other processes that can happen that aren’t talked about as much, but are pretty important when talking about the hydrologic cycle.

Liquid water evaporates into a gas, and gas can condense back into a liquid. Liquid water can freeze into ice, and ice can melt into a liquid. We are all very familiar with these processes, and how to get from one form of water to another. But did you know that there are also direct links between the gas and solid phases of water, as well? You may not know the technical terms for them, but you’ve definitely seen them in action.

Deposition and Sublimation

Deposition is the process by which water vapor turns directly into a solid, and sublimation is the process by which a solid turns directly into a gas.

Think about the freezer in your kitchen. It’s a pretty cold place. If you put water in an ice cube tray and place that tray in the freezer, the water freezes. That’s it. Right? Wrong.

Sublimation and deposition are also taking place in your freezer, and you’ve probably just never thought about it.

Have you ever noticed, if you leave the ice cube trays in your freezer for too long, the ice cubes start to shrink? You don’t have to twist and turn the tray to get them out; they’re smaller than the mold, so they just slide right out. There’s obviously less ice in there, but there’s no way it melted in the freezer. It’s sublimation. There’s a lot of complicated chemistry that goes into why this happens, but basically, sublimation is a specialized state of change that allows a substance to go directly to the gas phase from a solid.

Deposition is the exact opposite of sublimation. It’s a specialized state of change that allows a substance to go directly to the solid phase from a gas. This also is occurring in your freezer. If you go to your freezer, move everything out of the way, and look at the very back, you’ll probably see some solid ice “growing” back there. Unless you threw some liquid water in there and allowed it to solidify, you might be wondering how the ice got there. Deposition is occurring. The water vapor is depositing on the walls of your freezer in a solid form. Pretty neat stuff, right?

But how does this relate to the hydrologic cycle? Well, sublimation can and does occur in specialized moisture and wind conditions or at very high altitudes, like on the top of Mount Everest. Nothing on the top of Mount Everest is ever going to melt, but the precipitation that falls there recycles through the atmosphere by sublimation.

Speaking of recycling, check out how the two big arrows on either side of this picture make it look like all these processes are kind of happening in a loop. What allows this process to continue in a cycle instead of being halted at the ocean is advection. In the water cycle, advection is the movement of water through the atmosphere. It’s the process that allows water from the ocean to be recycled and make its way to our drinking fountains. It also allows water that was once deep underground to be recycled as snow on top of mountains.

Now that we’ve talked about the hydrologic cycle, let’s go over a couple of review questions to really drive these concepts home.

1. Which process is the evaporation of water from plant leaves?

- Plant uptake

- Sublimation

- Transpiration

2. What is the difference between percolation and infiltration?

- Percolation occurs in oceanic crust, while infiltration occurs in continental crust.

- Percolation is the downward movement of water through porous or cracked rock, while infiltration is the downward movement of water through earth’s subsurface.

- Infiltration is the downward movement of water through porous or cracked rock, while percolation is the downward movement of water through earth’s subsurface.

Okay, that’s all for this review! Thanks for watching, and happy studying!