Gastrointestinal System

Hey guys, and welcome to this Mometrix video about the gastrointestinal system.

The gastrointestinal system is also called the digestive system for an obvious reason. That’s where all the facets of digestion take place. That means everything from the way food comes into our body, how our gastrointestinal system breaks down that food, and how waste exits our body. It’s a complicated but important process. So let’s take a look at our gastrointestinal system in more detail.

GI System Importance

Our gastrointestinal system does more than digest our food. Our bodies need nutrients from food and water for us to stay healthy and survive. Our gastrointestinal system breaks down food into very small pieces that can be absorbed by the body and used as a sort of fuel we need to function. Major nutrients include proteins, which help fight infections and make healthy cells. Carbohydrates provide a source of energy. Minerals perform several functions, like keeping bones strong with calcium or providing an adequate supply of the iron that helps transport oxygen in our blood. So yes, digestion is important, but our gastrointestinal system does so much more.

So what happens once we ingest our food? Let’s find out.

GI Tract

We all have a gastrointestinal tract, called the GI tract. This long passageway starts at our mouth and ends at our anus. Think of the GI tract as the entrance and exit point of our food. The GI tract is also called the digestive tract or the alimentary canal. Yes, the GI tract passes a number of solid and hollow organs, and we’re going to take a closer look at those now.

Solid and Hollow Organs

The GI tract has three solid organs: the liver, the gallbladder, and the pancreas. The mouth, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestines, and anus are the hollow organs. Those hollow organs push food through our bodies via a process called peristalsis. It’s the push and pull that allows food to move from one muscle to another. The muscle behind the food contracts and the muscle in front of the food relaxes, allowing for easy passage.

That’s the short of how food moves through the body. Now we’ll take a journey through the gastrointestinal system and a more detailed look at its parts.

Mouth

We’ll start at the mouth, the place that chews and ingests our food. After chewing, we swallow, and the tongue plays its important role by pushing the food into our throat.

Epliglottis

The epiglottis, a small flap, covers the windpipe so food doesn’t get stuck there.

And now that we’ve swallowed the food, the digestive journey starts.

Esophagus

After we swallow, the food passes through the esophagus and at that point peristalsis begins.

When the food reaches the end of the esophagus, it passes through the lower esophageal sphincter and then into the stomach.

Have you ever gotten heartburn or acid reflux? You see, the sphincter is supposed to stay closed, so food doesn’t back up into the esophagus. When the sphincter relaxes at the wrong time, and food backs up, well, you get that heartburn feeling.

Stomach

But if everything goes as it should, the food has now made its way into our stomach, and that’s where it goes for a nice digestive swim. Digestive juices coat the food and liquid and break them down so they can continue their journey through our bodies.

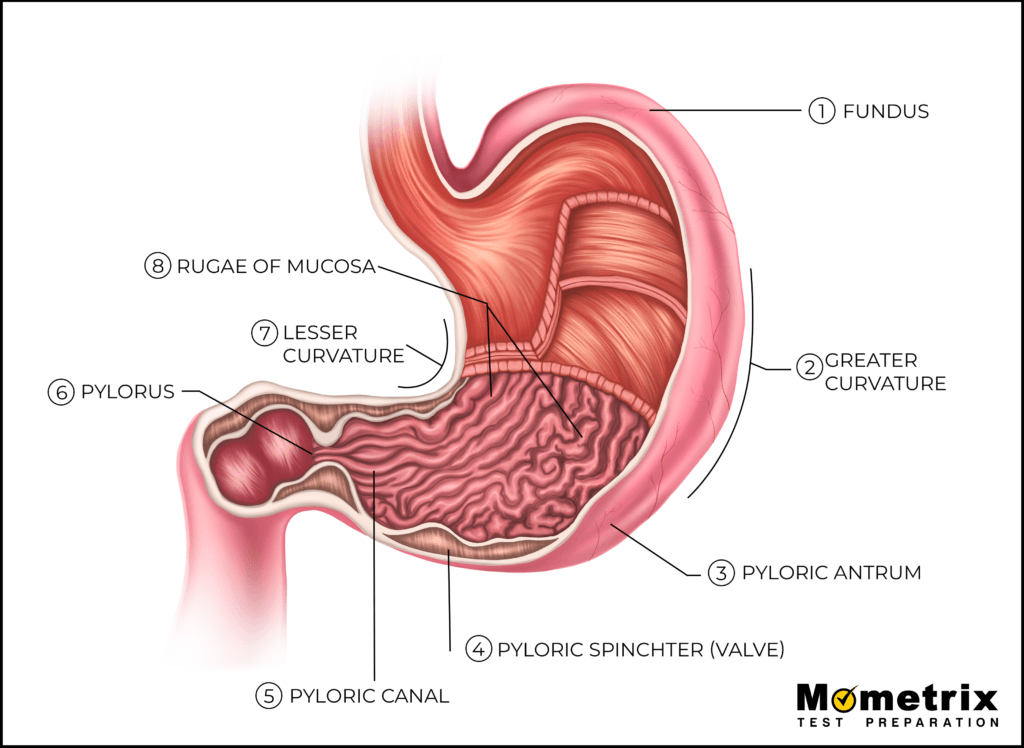

But before we continue along our journey, we need to talk a little more about the stomach, a single organ that has five different parts.

Parts of the Stomach

Those parts are the cardia, the part of the stomach closest to the esophagus; the fundus, which is located next to the cardia and is the upper part of the stomach; the main part of the stomach, called the body; the antrum, the lower portion of the stomach where food and liquid mix with digestive juices; and the pylorus, which lets food pass from the stomach into the small intestine. Remember the pylorus, because that plays an important role in our next stop, the small intestine.

Small Intestine

Once in the small intestine, nutrients head into the bloodstream, and waste starts the process of moving out. The small intestine has three sections that we’ll briefly talk about here.

Duodenum

The first section, the duodenum, is the smallest section. When food passes from the stomach, it enters the duodenum through the pylorus.

Jejunum

The middle section of the small intestine, the jejunum, absorbs sugar and amino and fatty acids before it moves on to the final part of the small intestine.

Ileum

The last part, called the ileum, absorbs nutrients that were not digested by the jejunum. Those nutrients include carbohydrates, minerals, and fats.

As food leaves the small intestine, it enters the large intestine.

Large Intestine

So if the small intestine is about 23 feet in total, why is the large intestine labeled “large” if it’s only about six feet long? You see, the large intestine, at three inches, has a larger diameter than the small intestine, which is just about an inch. The term large intestine refers to the larger diameter, not the total length.

The large intestine takes food, breaks it down even further, and turns it into waste. There are several sections of the large intestine that participate in this process, and we’ll go over those here.

The large intestine has four parts: the ascending colon, the transverse colon, the descending colon, and the sigmoid colon.

Ascending Colon

The ascending colon is the beginning of the large intestine and has two important parts: the cecum and the colic valve. The valve is at the end of the ascending colon and separates the cecum from the small intestine. The valve prevents food and other materials from flowing back into the small intestine.

Transverse Colon

The process of fermentation takes place in the transverse colon. As food leaves the ascending colon and enters the transverse colon, fermentation further breaks down the food by removing water and nutrients. Once the fermentation process finishes, the remaining waste forms.

Before we talk about the next step, here’s another note about the transverse colon. Two arteries, the medial colic artery and the inferior mesenteric artery, provide a constant supply of oxygenated blood to the transverse colon. Why? Because that blood flow keeps the intestine healthy and prevents illnesses like intestinal ischemia.

Let’s continue our journey. Food has moved from the small to the large intestine and has made its way to the transverse colon. The next stop: the descending colon.

Descending Colon

The descending colon stores food before it’s emptied into the rectum. It’s also the point at which feces starts to become solid.

Sigmoid Colon

From there, waste enters the sigmoid colon, and that’s where waste solidifies. The muscular walls of the sigmoid colon contract to push feces into the next part of the gastrointestinal system: the rectum.

Rectum and Anus

The rectum acts as a holding tank for waste. The rectum holds feces until it’s ready to be expelled. In other words, that’s where waste stays until you’re ready to use the bathroom. From there, the waste exits through the final stop in the gastrointestinal system, the anus.

So that’s the journey food takes.

Now, let’s take a closer look at the enzyme production in the gastrointestinal system.

Enzymes

Carbs, proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids are all major elements in biological molecules. Life can’t exist if the body is missing any one of these molecules. So it’s no surprise they each play a role in the gastrointestinal system. Here’s how.

Enzymes that Break Down Carbs

There are three enzymes that help break down carbohydrates. The salivary amylase enzyme in the salivary gland helps break down starches and sugars. The process takes place in your mouth. Pancreatic amylase in the pancreas completes carb digestion and produces glucose. Lastly, the maltase enzyme in the small intestine breaks down disaccharides into single sugars.

Enzymes that Break Down Proteins

There are also three enzymes that help break down proteins. Pepsin, which is produced in the gastric gland, and trypsin, produced in the pancreas, both help digest protein in food. Peptidases, produced in the small intestines, also break down proteins, but in this case, for the purpose of recycling amino acids.

Enzymes that Break Down Nucleic Acids

Nuclease and nucleosidase and two enzymes associated with nucleic acids. DNA and RNA are the two main nucleic acids. Both enzymes are produced in the pancreas.

Enzymes that Break Down Lipids

Lipids, those fatty and oily substances in the bloodstream, are broken down by lipase and bile salt. Lipase is found in the pancreas, while the liver makes bile salts and the gallbladder stores it. Technically, bile isn’t an enzyme. It’s a salt that mixes, or emulsifies, lipid into fatty acids.

We mentioned cells and patches, and they also play an important role.

Cells and Patches

Chief cells, located in the stomach, convert pepsinogen to pepsin, which we already know helps digest protein. Goblet cells, found in the respiratory and intestinal tracts, secrets mucus. Parietal cells are crucial to the production of hydrochloric acid (HC1), which helps with digestion. Finally, Peyer’s patches, the lymphatic tissues found in the ileum of the small intestine, protect the gastrointestinal tract from pathogens.

So that’s our overview of the gastrointestinal system, the system that acts as an entrance for food and an exit for waste. As we noted, the gastrointestinal system also plays a role in breaking down nutrients that become fuel for our body.

- “Your Digestive System & How It Works.” NIDDK. May 11, 2023

- “Your Digestive System.” WebMD

- “Digestive System Anatomy, Area, and Diagram | Body Maps.” n.d. Healthline

- “Descending Colon Anatomy, Diagram & Function | Body Maps.” 2018. Healthline

- Bradford, Alina. 2016. “Colon (Large Intestine): Facts, Function & Diseases.” Live Science

- Mayo Clinic. 2018. “Intestinal Ischemia – Symptoms and Causes.”

- Hoffman, Matthew. 2009. “Picture of the Intestines.” WebMD

- “Food Reactions: The Digestive System.” n.d.